For 93-year-old veteran Richard Lemay, the events of WWII sometimes feel like a dream. In September 1942, the former Air Force air frame mechanic joined the Canadian Forces with his brother, Edward. He said it felt like he had a duty to support the allies.

Lemay was recently awarded the rank of knight of the French National Order of the Legion of Honour. It’s France’s highest award. On the 70th anniversary of D-Day, in 2014, French president Francois Holland pledged that all of the servicemen who fought alongside France would receive his nation’s highest honour.

Of the approximately 1.1 million Canadians who served in the Forces during WWII, fewer than 88,400 remained living as of early 2014. Veterans Affairs Canada reports that most of these WWII veterans are over the age of 90.

Lemay said that he felt honored to be recognized for his war efforts. It also brought back many memories of a time that was often dark and violent.

“It’s more or less in recognition of all of the people who gave their lives and of the veterans who have already died,” said Lemay, from his home in Hawkesbury, where he lives with Doreen, his wife of 66 years.

When Lemay joined the Air Force he was 18 years old. He left Hawkesbury for training and he was then sent overseas to join the fighting. Between 1943 and 1945 he traveled across Europe, following the fight from England to Scotland, France, Belgium and Germany. His final posting was in Holland.

“I was assigned to one particular aircraft. It was a “mosquito.” It was our job to keep the boys flying. I lost four of them. At one point, there was not one aircraft left,” said Lemay, who paused for a moment to reflect on the pilots who went down in the aircraft he worked so hard to keep in the air.

As a member of 409 Squadron, Lemay traveled to where the fighting was most intense. This often meant flying planes out of airports that had been hit by so much artillery that the tarmac resembled Swiss cheese.

“We had to put a mesh net over the holes in the tarmac because of all of the bomb strikes,” said Lemay.

He said that the only thing worse than the bombardment that hit London, were the “buzz bombs,” which would fly silently through the air and level anything they hit.

“All of a sudden, we see these things flying in the sky. They were the V-1 buzz bombs that were fired out of Germany and headed towards London. When they ran out of gas, they would fall to the ground and explode. One hit a tree about 200 yards away from our group in “B” flight dispersal. It exploded and broke some windows. The V-1 bombs didn’t make any sound. They would shoot three. If you heard the bang, that was the first one hitting. Then there would be a second one. If you heard the third one, then it meant that you were still alive,” said Lemay.

The accommodations could be just as dangerous as the fighting. When his unit was stationed in France, they happened upon a beautiful old Chateau that had once housed Hitler.“The first person went in and he used the bathroom. He was killed by a bomb that had been planted inside. We didn’t use the bathrooms after that,” said Lemay.

Travelling from town to town, Lemay said the devastation was hard to comprehend. Due to extensive bombing, many of the towns had been totally leveled. “We were passing people who were coming back to these towns and all that was left were a few half-walls where there used to be buildings,” said Lemay.

In 1944, Lemay’s unit was sent to the continent. That’s where they ran into a major logistical problem that Lemay said got many Canadians killed. “When we arrived, we were issued army uniforms, because the German uniforms and our navy blue air force uniforms were very, very similar. When the Americans joined the fighting, they were shooting at the Allies. They thought we were Germans. In our brown army uniforms, they stopped shooting at us,” said Lemay.

Near the end of the war, things began to change. Lemay said that there was a feeling of hope.

“I was on the airfield one day when two Germans came walking towards me. They were carrying their luger guns, but they were holding them against their bodies, not pointed at me. They gave themselves up and surrendered. They asked to meet with my commander. At that time, near the end of the war, the Germans didn’t want to be captured by the Russians, so they were giving themselves up to the Allies,” said Lemay.

When the war ended, Lemay’s final task was to help guard two of his fellow service members, who were awaiting court martial.

“I was one of six men set to guard them. We were in Germany and one night they up and disappeared. The military police (MPs) came with us to Little France, where we picked them up and brought them back. They were behind bars in England when we left,” said Lemay.

On arrival in France, there were parades and celebrations to mark the end of the war. One of the most symbolic celebrations was performed by a pilot in Lemay’s unit who flew his plane between the columns at the base of the Eiffel Tower.

It was a difficult time for Lemay. He said that he was happy to see the war end, but he was finding it difficult to leave the unit whose members had been his family for the past three years. At the end of the war he lost touch with his friends. He said it felt too difficult to remain in contact. He says it would be nice to hear from them again.

After spending almost three months in England, Lemay boarded the RMS Queen Elizabeth ship and headed for home.

“(Former British Prime Minister Winston) Churchill was on the ship with us. He came over with us and gave a number of speeches. When we landed in New York, the Andrews sisters were signing on the docks,” said Lemay.

- WWII veteran Richard Lemay is seen here holding an image of what he looked like as a young soldier during WWII. (Photo: Tara Kirkpatrick)

- A blitzed building, as seen in the 1940s. (Photo: 409 Squadron, Canadian Air Force)

- At the border to Germany, Allied Forces are advised not to fraternize, Photo, mid 1940s. (Photo courtesy 409 Squadron, Canadian Air Force)

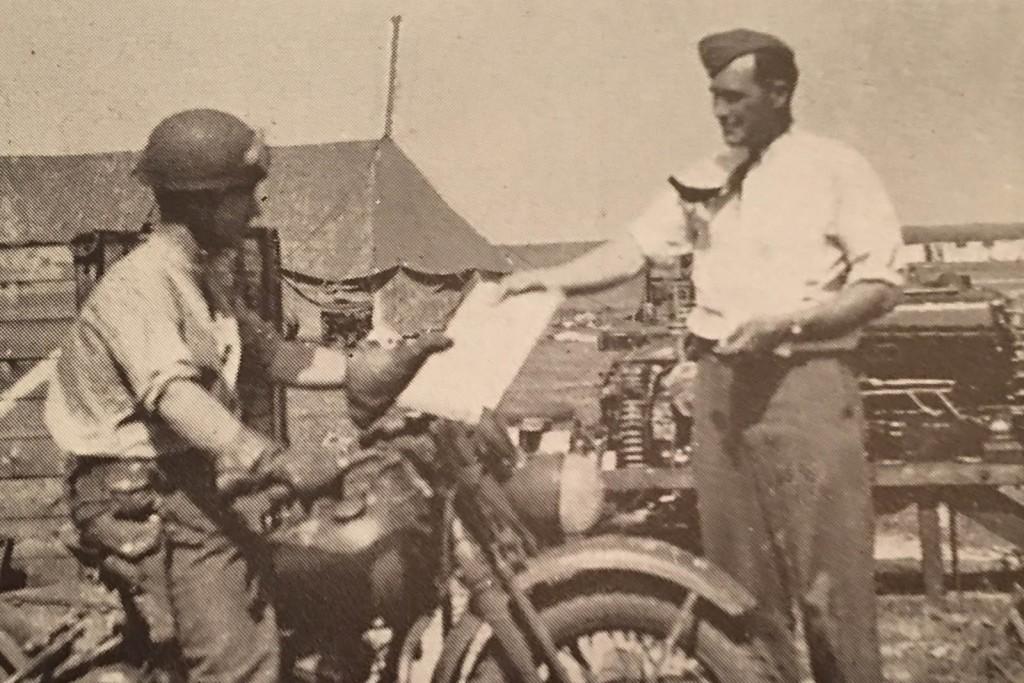

- A member of the 409 squadron is seen riding a motorcycle during WWII. (Photo courtesy of 409 Squadron, Canadian Air Force)

- A crashed plane is seen in a historic photo provided by the 409 Squadron, Canadian Air Force.

- WWII veteran Richard Lemay is seen holding the medal awarded to him by the French Government. It awards him the rank of “Knight of the French National Order of the Legion of Honour”. (Photo: Tara Kirkpatrick)

- Members of the 409 Squadron hold up a flag beside a Nazi aircraft during the fighting in WWII. (Photo courtesy of 409 Squadron, Canadian Air Force)

- “Mosquitoes” were the type of aircraft that WWII veteran Richard Lemay maintained during the war. (Photo courtesy of 409 Squadron, Canadian Air Force)

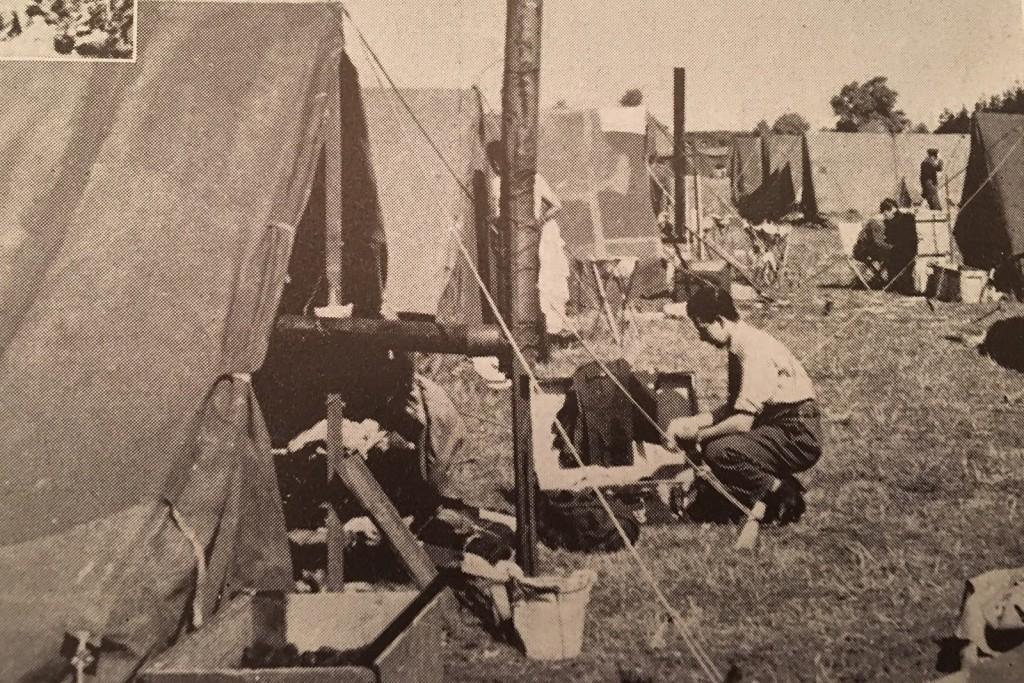

- Living conditions for the 409 Squadron were primitive during WWII. During the spring, veteran Richard Lemay said the mud could get to be over a foot deep. (Photo courtesy 409 Squadron, Canadian Air Force)

- The GIlze Reijen Airfield during WWII. (Photo courtesy of 409 Squadron, Canadian Air Force)

- At the end of WWII a Canadian pilot with the 409 Squadron flew a plane below the Eiffel Tower. (Photo: 409 Squadron, Canadian Air Force)

- A sketch of WWII veteran Richard Lemay, shortly after he joined the Canadian Air Force in 1942.